![]()

Ouyang Yu’s new biog for 2024

Ouyang Yu came to Australia in mid-April 1991 and has since published 146 books of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, literary translation and criticism in English and Chinese languages, including his award-winning novels, The Eastern Slope Chronicle (2002) and The English Class (2010), his collections of poetry, Songs of the Last Chinese Poet (1997), and Terminally Poetic (2020), which won the Judith Wright Calanthe Award for a Poetry Book in the 2021 Queensland Literary Awards, his book website: www.huangzhouren.com and his bilingual blog: youyang2.blogspot.com

He was shortlisted for the Writer’s Prize in the 2021 Melbourne Prize for Literature and won the Fellowship from the Australia Council in late 2021 for writing a documentary novel. And his sixth novel, All the Rivers Ran South, is coming out in mid-2023 with Puncher & Wattmann and his first collection of short stories in English, The White Cockatoo Flowers, forthcoming in 2024 with Transit Lounge Publishing.

A short biog

Yesterday as I started reading Brian Castro’s Drift, it crossed my mind that here was an author who should be in serious contention for the Nobel Prize in Literature. I have not the faintest idea how authors get nominated, but based on the works of the Nobel Prize winning authors that I’ve read, I think that there are three authors writing in Australia today whose work the Nobel Prize Committee should know about. They are Castro, Gerald Murnane and Ouyang Yu.

Lisa Hill on Ouyang Yu

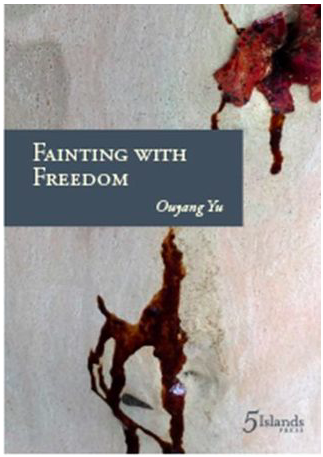

In form and style his poems are typically full of disruptive, unexpected lines, deploying enjambment, malapropism, skilful grammar (as well as wilful disregard for grammar) in service of profundity, humour, and intellectual interrogation. Moments emerge from Yu’s work as a translator and as a language teacher, and his fascinations capture not only an other’s perception of his second language and culture, but also a revision of his first language, and glimpses into parallels (as well as enormous divergences) between the two. There’s something enormously heartening about reading such a living, adventurous book published in English in Australia that can nonchalantly presume the relevance of a treatise on individual Chinese words or characters, or their relationship with English.

Michael Aiken on Ouyang Yu’s Fainting with Freedom (now out of print)

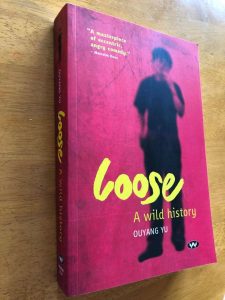

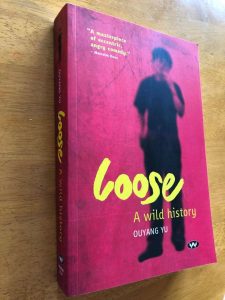

This is an excerpt from Alex Miller’s launch speech for the novel, Loose, a Wild History:

While I was reading LOOSE there were times when it reminded me of the American writer Theodore Dreiser’s very loose history of himself, DAWN. Moments when LOOSE had that same eager tone of searching, searching, searching, to connect the inner life to the realities of the outer life, as if membranes of purpose and meaning might exist for both in the culture which, if he rejected sufficient of the commonplace, might eventually make their appearance to him. But no Australian book came to my mind. LOOSE talks tough. It is not written in the diplomatic language of Australia/China cultural friendship societies. LOOSE is the underbelly, the private interior voice of paranoia and mistrust, ambivalence and misunderstanding, the voice of just how difficult it really is to speak meaningfully of Australia/China cultural exchange at the level of the life of one individual whose history stands, painfully and problematically, across both cultures. “I am still young,” the author laments on page169, “ but absolutely useless in this society that has trashed me through conspiracy.” Strong words. LOOSE asks how is it possible to belong in both cultures. In the process of doing this it challenges our most dearly held beliefs and hopes of cultural influence and exchange with China. LOOSE questions the very basis of Australia’s place in Asia. It derides the hypocrisy of diplomatic speak, and it does it often with brilliant humor and even more often with vicious satire. LOOSE does something else that is just as important as this, and perhaps even more challenging for Australian writers (and I am one of that peculiar breed). I’ll get to this other thing in a minute.

Loose, a Wild History

Sally Fitzpatrick on Ouyang’s THE ENGLISH CLASS:

The effervescent energy of this novel, and the charm of its innocent protagonist, compel interest throughout the entire four hundred pages. Reminiscent of the picaresque hero Don Quixote, the hapless truck-driver, Jing, tilts at the windmill of the English language as he bounds around in the Unique, his rattling, truck-without- breaks. More aptly perhaps, Jing resembles Sun Wu Kong, the famous Monkey King, hero of the Chinese classic, Journey to the West, who lampoons the phantasmagorical world of Chinese Buddhist and Taoist belief.

The English Class